All of us here responded to an invitation to dialogue together around the topic of Peace Building and Conflict Transformation, but from a particular lens: that of Postcolonialism and Indigenous Christianity. On this journey that started at the beginning of December and takes us here to the end of March, we sought to name historical injustices and physical and intellectual forms of colonization; we listened to and learned from diverse narratives of Scripture; and, in a process of re-learning, we heard the voices and perspectives of many who have traditionally been marginalized and ignored.

We began with a call from our indigenous brothers and sisters of Memoria Indígena in Latin America to listen to their memories – because when we listen, we discover that the history of colonization and resistance continues to repeat itself in the lives of indigenous peoples today. Jocabed Solano placed before us some concrete questions that help us move in a direction of recognizing the indigenous churches and their cultural richness:

-

- How can we transform the traditional structures of theological education in its pedagogy and theology, which seek to dominate and do not give space to indigenous voices?

- How can we build a community of faith that recognizes diversity in the body of Christ?

- And what concrete steps promote an intercultural church?

Julián Guamán and Peter Wigginton showed us how indigenous communities can lead the Church in the task of reconciliation with one another, with God, and with the community of creation. The Kichwa people’s understandings of reciprocity in relationships and harmony within the created order invite us to interrogate our posture towards the land and the cosmos. Later on, Jocabed offered a similar approach, inviting us to a cosmic reconciliation, in which we are all invited to participate in the protection and rebuilding of our common home.

Then, Daniela Améstegui guided us as art opened our senses to the Andean world and experienced worship of God in the taste of maize, in the patterns of women’s weaving, in the sounds of the waves hitting the shores of Lake Titicaca, and in the rays of the sun at harvest. Her presentation stirred passions and ideas in each of us for what it might look like to encounter God in deeply contextual liturgy that reflects the stories and realities of people who have been marginalized.

In the words of Abdiel Espinoza, we saw the Son of God chopping tomatoes, stirring stew and serving plates overflowing in a tucked-away corner of Tijuana.

Read a summary and reflection on the forum launch, written by Tony Deik, here.

As we moved into January, we wrestled deeply with the colonization of land, practices, and knowledge that has come through things like the Christian mission enterprise and the Western university system. Alex Jones asked us the question: what would a postcolonial Christian university look like? Is it even possible, when the research money and the power are still concentrated in the traditional institutions? Martin Munyao revealed the historical colonization perpetuated in the name of Christian mission in East Africa, which dissolved indigenous cultural institutions and collectivism, setting up systems of hierarchy and individualism. A “white” theology and worldview became the default, ignoring local culture and context. In light of this, Martin called the Church to engage in the local, to let itself be changed by non-White realities, and participate in the political transformation of our societies.

We learned from Benita Simon and Ismael Conchacala about the ways in which the Church, to this day, can be a space that perpetuates violence against indigenous cultures, but alternatively, it can also be a space that awakens us to the richness of cultural diversity in our understanding of God and the world. This prepared us to learn from indigenous women about doing theology through indigenous art.

We explored processes of peacemaking within the Church, a peace that does not gloss over the systemic injustices and historic violence but engages in reconciliation by radically subverting power structures. Ruth Padilla DeBorstshowed us that this peace requires coming together with open, empty, wounded hands – the willingness of the Church to disentangle itself from colonial powers and live as a radically inclusive community. Al Tizon walked us through the processes of repentance, forgiveness and lament that is like rebreaking and resetting a broken bone and leads us into the possibility of true healing. Nina Balmaceda offered us a pathway toward reconciliation that requires us to actively seek justice and transformation as we ask the questions:

-

- Where are we going?

- What is happening here in our context?

- Where do we see signs of transformation and liberation?

- And why me or why us? What is our role in bringing reconciliation?

Then, we were invited to explore the realities of many brothers and sisters across the globe. Jayachitra Lalitha and Obed Manwatkar described to us the particular context of India and how the Gospel should be good news for the oppressed by the caste system, Dalits and OBC’s. We examined how Jesus himself subverted imperialism and how the Great Commission serves as a postcolonial act in its radical embrace of the “other.” Raphael Idialu portrayed for us the Nigerian context, offering Koinonia as a form of resistance when it brings together four key aspects: community relationship, partnership, communion, and the sharing of material possessions. From the quiet, peaceful ferment of Pentecostalism in and after the dictatorship in Romania, Beni Mocan offered the Church’s experience of peaceful protest, rooted in the love of the Spirit, as a powerful actor in the journey toward reconciliation.

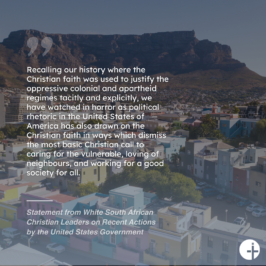

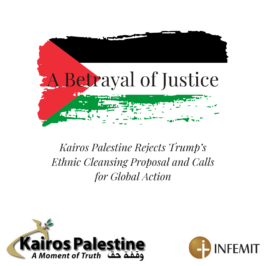

Finally, this week, we returned to the realities of ongoing colonization that plague our indigenous brothers and sisters across the globe. With a call to examine our nations’ problematic and oppressive histories, Terry LeBlanc showed us how indigenous people continue to be misrepresented, ignored, and oppressed in our societies today. Likewise, Shadia Qubti and Tony Deik helped us to understand the ongoing colonization in the lands of Palestine, aided by Christian Zionist theologies that fail to see God’s image in the Palestinians. Reconciliation for those who live in a constant state of colonial violence and oppression must include justice: true peace will be built on the rights and the restoration of the wellbeing of these communities.

To conclude, Tony showed us that our search for peace and reconciliation must be built on a transformed theology and view of the other. Like Paul in Acts, we are invited to recognize that God has made all in God’s image and that God’s redemption extends to everyone in an inclusive embrace.

So, what will it mean for us, as we move forward, to continue to listen to the stories of people on the margins? To deconstruct our understanding of theology, history, and the “other?” To resist ongoing colonization and seek justice? And to live out a radical, inclusive, reconciling community as the Church?

Leave a Reply