Part 1: English Transcript

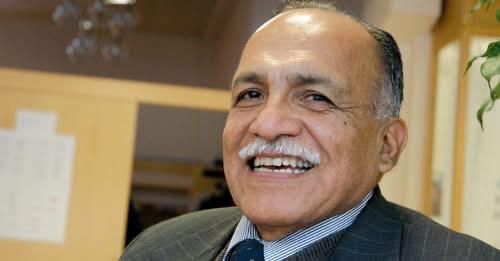

Julián Guamán

The concept of community in Quechua is the “ayllu.” That is the concept. The ayllu. Ayllu is like families in kinship relationship: but extended families, located in a territory, which has autonomy even in aspects of the administration of justice, economy, among other areas. But it means that: the community. In Kichwa, the ayllu.

On the one hand, this idea of community maintains that, basically, the human being alone does not exist, in the Andean or Quechua worldview. Rather, it depends on all else that exists. That is why some elements of this concept of community are so relevant, such as, for example, reciprocity or “ayni”, which is a work between families – of collaboration between families. The other concept that is used is the “minka” or “minga.” It is the concept for public works, if you will, community work, such as the building of roads, or to maintain the irrigation system, that is, works that benefit everyone, not only families. So, it is these two concepts of minga or ayni that are very concrete concepts of real life, but are essential to maintain the community, in dependence. The individual is not denied, but the individual does not exist without the community.

Therefore, the land is an inheritance for us. It is not a property, it is not a good, it is not a thing – because of this concept, which we will later relate to creation.

In contrast, in the Anabaptist world, it is interesting that Anabaptism has a reading of the Bible, an interpretation of the Bible based on this concept posed by Jesus himself. Jesus relates, builds, let’s say, develops a community of believers who will later be called “Christians” and Acts chapter 2, verse 40 (well, chapter 2 onwards), we see the great description of the first followers of Jesus: how they organized themselves, shared, and lived. To such an extent that a sector of Anabaptism opted for the community of goods, such as, for example, the Hutterites in the US and in Germany for a long time. It is an expression based on Acts chapter 2, 41 to 47.

So, there we see this community where there is solidarity, where there is fellowship, where there are economic and social dimensions. That is what is important to note in Acts and what is posed in the kingdom itself, what Jesus proposes as the kingdom of God, isn’t it? So, these elements coincide, they reflect the proposal of the Kichwa ayllu.

And in the particular case of Ecuador, in Chimborazo, where there were mostly Mennonite missionaries, although they never planted precisely Mennonite churches (but they were Mennonite missions), they were able to develop churches with a local, community style, avoiding dependency, a church of mutual protection, mutual solidarity, etc. So, in this model, I find an element that can help us. Regarding creation, it is interesting that Anabaptism proposes creation “care,” based on Genesis chapter 2, and not based on Genesis chapter 1. In Genesis chapter 1, we find in 1:26, 27, 28 the subjugation and domination of man over the rest of creation, because the Bible says: subdue, rule over the fish, and so on. But Anabaptism reads and bases its concept of care of creation on Genesis chapter 2, verse 15, if I’m not mistaken, or 9. There we find these two concepts: cultivating – cultivating implies an economy, it means care, protection, thinking, analyzing nature, understanding nature, and therefore, also, coexistence. Ultimately, it proposes coexistence by posing the themes of cultivation and care. So, we find the idea in those themes.

On the other hand, when we examine these elements from purely Kichwa worldview, far removed from Christianity or the influence of Christianity – any type of Christianity – it also suggests that the human being, that is, the “runa,” in Kichwa, the runa is the human being, runa is part of creation. It is neither superior nor inferior to creation. Therefore, it cannot dominate; neither can it be mastered. It does not suppose control, domination, at all. Rather, it suggests coexistence, and that concept obviously also coincides with the Anabaptist view, which also has a lot to do with the Judeo-Christian narrative of Genesis chapter 2.

Peter Wigginton

And to follow up on what brother Julián is telling us …

He had mentioned previously that this approach, this essence, of Anabaptism has three parts: Jesus, community, and peace. This approach to peace comes from what Jesus teaches us about reconciliation. So there is an Anabaptist author, Palmer Becker, who talks about reconciliation and develops it in three parts: a reconciliation that every human being has with God, that each person has this relationship with God and is reconciled to God. Also, there is reconciliation between brothers and sisters in community. And we can expand it to the point that there is reconciliation in the world.

So the church is led to go out into the world and work on that reconciliation. But that does not stop only with human beings, as brother Julián says. This reconciliation, we are sent to be reconciled with everyone, but we are also led to be reconciled with nature, with God’s creation.

And I want to share a little anecdote. When we were working in Chimborazo, in Riobamba, we were working with some colleagues with my father, doing some sustainable agriculture workshops. We were working with leaders from different churches, and we did some workshops on, on the one hand, recovering ancestral agricultural practices, but, on the other hand, also different ideas of how to improve their agricultural work. And every morning we did a Bible study before going to the field to do the work. We sat in a group, and we read this verse from Genesis 2, where it says that God sends Adam and Eve to take care of and work the land. And we asked the brothers, indigenous leaders, is there a way that you can work your land without taking care of it? Or can you take care of it without working it? And they all looked at us like I was asking something weird. “What?” They said, “no, there is no way to work our land without taking care of it,” that is, both things must go hand-in-hand.

For me, that also leads me to this idea of reconciliation. We can’t have a reconciliation between brothers and sisters and with nature without this… It’s like a complete package. We must do the work of helping one other among brothers and sisters, feeding one another, obtaining the fruits that creation gives us, but we cannot do this while neglecting creation, because this can have very complicated repercussions for other people, mainly marginalized people, such as indigenous groups, which are in the areas that are most affected by the destruction of our creation.

Part 2: English Transcript

Julián Guamán

I think that, well, in the Kichwa world, I would say that there is no concept like reconciliation, but, there is a concept that is characterized as harmony, as balance, as a bridge.

This is important, why? Because in the Kichwa worldview, we privilege the concept of parity – the concept of parity: That is to say, life is made up of pairs.

Take for example: death, there must be something that allows us to understand life, just as life is necessary to be able to understand death. Or the cold and the heat. In other words, life as such is made up of pairs. Or better said, two things in a pair, generate life, or are life. These, therefore, are necessary in the Kichwa narrative or worldview, which obviously is not based on duality. It is not dualism. Rather, when, say, one of the parts is in excess, this generates an imbalance, disharmony. Therefore, the duty of the human being is to put things in parity, or in balance, in a bridge. And the philosophical word for that is “chakana” which comes from the word chaka: which is a bridge, a nexus, a relationship; and na: the act of making. So, balancing, the act of bridging, the act of keeping in harmony. That is, therefore, maybe the central point. And what we call in Kichwa, well, “Runasimi” is the language, “Runashimi” or “Runasimi,” but we usually call it Kichwa. In the Kichwa language, we say: there is only one word that brings us together, it is the “pacha.” Pacha is space and time, which are two elements that are related, that are interrelated and produce life.

So, that could somehow coincide or be related to the concept of reconciliation, because the concept of reconciliation from the Judeo-Christian perspective is purely unidirectional. That’s why, the interpretation given by Anabaptism is bidirectional, because it is a thing of God; And it is because of the gesture of God’s love, who is reconciling with humanity, that human beings also follow the divine example of reconciliation. But, also, the reconciliation that comes from God toward humanity transcends because it is also reconciling with creation. And that is what Psalms says, that is what is also found in [Romans 8], where it says that creation “groans” – groans in pain waiting to be redeemed. Without being redeemed, nature, creation. This concept is interesting. But God, through Jesus Christ, is going to reconcile and also redeem nature itself.

Peter Wigginton

We think of this idea of reconciliation, which comes from the word “council,” from being together, but perhaps we ought to emphasize that it requires effort. That reconciliation is not something that comes like that, in Bolivia, we would say by “chiripazo” which means only by chance, we assume the work that we do. Rather, it has to be a central work for Christians, it has to be a striving and a focus of our work.

For this reason, we think within Anabaptism that this reconciliation of God and this salvation that we have through Jesus Christ must be worked out in community. So, how can I be reconciled to God if I am not reconciled to my brothers, my sisters and to God’s creation? And, in the same way, if I am well and reconciled with my community and with my brothers and sisters, that likewise helps me to be more reconciled with God.

Julián Guamán

We could say that the concept of reconciliation is like “living together”, because I understand when I read the Bible and when I practice faith, that God takes initiative to live with community, with humanity, with God’s creation – which is humanity. So then, reconciliation can exist within a life together. And that living together implies interrelation, reciprocity, harmony, balance, many other concepts, but, in the end, it is living together. And reconciliation perhaps translated into a much more Andean language, much more Kichwa language, is that: living together. God takes the initiative to live with humanity through Jesus Christ. Which certain sectors of Christianity call salvation. We prefer to call it reconciliation. Others call it – we also call it living together. Or, in a language clearly reflecting the Kichwa worldview, the Kichwa narrative, we would say that it is chakana, that is, balance, harmony.

Or, in much more economic term, “sumak kawsay”, the “good life”; also, some would call it the “good news.” The good news is the living together that God proposes and that God lives with us through Jesus Christ.

Leave a Reply