English transcript

Video 1: A Little Bit of Context

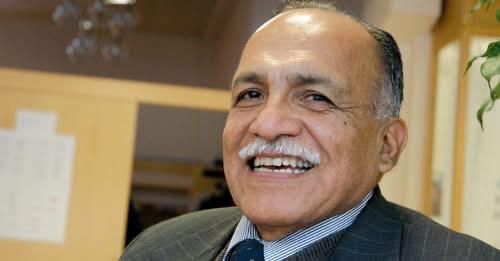

Shadia Qubti

So my name is Shadia. My journey to this point – I think my experience growing up in Nazareth as an evangelical, I was introduced to the work of reconciliation as a participant, initially, and in a context that’s full of conflict, I think my faith experience has shown me how we can be a model of peace, a model of reconciliation, through our faith. So I started working into the work of peacemaking primarily with faith communities and from there, kind of, my journey grew into a larger experience of peacemaking, and how do we navigate, kind of, our faith with, with our context, especially in an intractable conflict like Israel or Palestine. So most of my work in this area has been working with para-church organizations, local, and then moved on to international organizations, but really the main question has been: How do we implement the mission of God in peace making, and with our respective contexts?

Tony Deik

I grew up in Bethlehem, I was born in Jerusalem, but grew up in Bethlehem, so that makes me a Bethlehemite, because where where you’re born in our context does make a difference, it’s where your family is from. I grew up in a Roman Catholic family but I had a living relationship with the Lord as a, as a child, and then when I grew into adolescence, I gradually left faith, and by the time I was at university, I completely abandoned God and the church, and I became a committed Christian again in 2010- 10 years ago and it was through through a vision actually, through a, I would say a supernatural experience, that brought me back to faith, and I was immediately attracted to the evangelical church, and to the evangelical faith because of their focus on Jesus, on the cross, and on Scriptures, and at that point in my life I only wanted the Bible, and I only wanted Jesus. So I joined an evangelical church and there is where the challenges started.

So I discovered that a lot, many evangelicals believe that God gave Israel the land, that Israel has a divine right to our land, to Palestine, and I was introduced to Christian Zionism when I became evangelical. Previously if you would ask me if you would mention Christian Zionism I would think of it as a cult like Jehovah witness, somewhere at the at the periphery of Christianity. And then when I became evangelical, I discovered that it’s mainstream, it’s part and parcel of evangelical theology. So that that was a big stumbling block in my Christian walk, and I would say it it still is a big challenge, a huge challenge, but by by God’s grace and the witness and the writing of many evangelical scholars, especially Palestinian Christians,I was encouraged in my faith, and probably if it wasn’t for the witness of, and the writing of many evangelical theologians from Palestine and elsewhere, I would probably have left faith. I mean, Christian Zionism for me does not represent Christ and this is not a religion that I want to belong to if God is like this, preferring one nation over the other, doing real estate and dividing land based on ethnicity. I mean who wants to belong to such a group, no? So by God’s grace, I’m still a Christian and following Jesus, and now I have dedicated my life to the study and the teaching of the Scriptures, in particular. This is where my calling lies.

So when I used to give presentations, especially in mission contexts and prayer meetings, and etc., people would ask me, “please just put a map of Palestine! Where exactly is Palestine?” So unfortunately, it’s very hard like other countries, just to put a geographic map and say, “well this is Palestine.” If one wants to put Palestine on the map, we need to speak about history and geopolitics a little bit.

So this is a historical geopolitical map of Palestine, and the first map here on the left is Palestine before the establishment of the state of Israel. And just to give you an idea, in the 19th century, more than 95 percent of the population of Palestine was Arab. The 1878 census, the ottoman census of 1878, shows that around 86 to 87 percent of the population were Arab Muslims and around 10 percent Christians and 3 percent Jew -Jewish. And what happened is that towards the end of the 19th century, particularly 1896/ 1897, a movement by the name of the Zionist movement was established. It started with Theodore Herzl with the publication of his book Der Judenstaat in 1896, and then the first Zionist congress of Basel, in Basel, in Switzerland in 1897. And that congress basically decided on colonizing Palestine, on facilitating Jewish, mass Jewish immigration to the land of Palestine with the aim of establishing the Judenstaat, the Jewish state, on the land of Palestine.

So after the the establishment of the Zionist movement, the population, the Jewish population started increasing dramatically and in 1917- 1917 is a major milestone in our history. Britain which was a world power back, then offered in the Balfour declaration, Palestine as… or offered the Zionist movement Palestine, for them to establish their state there, their nation-state. And in 1917, the percentage of the Jewish people were around eight to nine percent, and after, that after the Balfour declaration, especially in the 20s and particularly in the 1930s, hundreds of thousands of European Jewish immigrants flooded into Palestine. In the 1930s, alone more than 200,000 Jews immigrated to Palestine, and they didn’t immigrate to live alongside Palestinians in one state. They immigrated to establish their own state on a land that is occupied by people from other ethnicities, the Palestinians. So you’ve got this dramatic increase in the Jewish population because of a colonial project that intended to encourage mass Jewish immigration to Palestine, and that’s still ongoing today. If you are a Jew, you’ve got the right to immigrate to Palestine.

So by 1946, the Jews became around one-third of the population of Palestine- 33 percent, however they only owned six percent of the land. And two-thirds of the population who were Palestinian Arab, they owned 94 percent of the land, so what happened is that in November 1947, the United Nations offered a plan known as Resolution 181- the United Nations Partition Plan, and they proposed to partition Palestine and to give the Jewish immigrants, who only owned six percent of the land and who were only one-third of the population, to give them 56 percent of the land of historical Palestine. And to leave the indigenous population, the Palestinians, with 43 percent. This is Resolution 181. of course the Palestinians rejected. This is their homeland, and how would you give newly immigrated people who only own six percent of the land, how would you give them 56 percent of your homeland? The Zionists on the other side celebrated this. However, Ben-Gurion, who later became the first Prime Minister of Israel, said that, ‘we celebrate and recognize the U.N. resolution, the U.N. plan, but the borders of our state will be determined by force, and not by some U.N. resolution.’

So this resolution happened in November 1947, and immediately after this resolution, in December 1947, the Zionist terrorist groups who later became officially part of the Israeli defense force, they started executing what is now known as Plan Dalet, which is a plan that was planned beforehand, since at least March 1947, and they started the planning of course, from the 30s, and et cetera, but it was set and and clearly planned and clearly finalized in around March in 1947. They immediately, one month after the U.N. Resolution 181, they immediately started implementing this plan and going village after village, depopulating villages and massacring people and pushing them out of their land, and as a result of this, this is what we in our Palestinian memory we call the Nakba, the catastrophe, which started in 1947, end of 1947, and ended in 1949. And in this, from 1947 to 1949, the Zionists depopulated more than 500 Palestinian villages and kicked out more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homeland, and they ended up taking 78 percent of the historical land of Palestine. So they were given by the UN in 1947, 56 percent of the land, and they ended up taking, like Ben-Gurion foretold, 78 percent of the land.

Now when you hear the word “Palestinian-Israeli conflict,” no one is talking about the 78 percent of the land. Since 1988 at least, with the declaration of the Palestinian Independence, the Palestinians recognized the two-state solution, they recognized Israel rights, Israel’s right to exist, and they only demanded 22 percent of their homeland to establish their state. So what the indigenous people of Palestine are asking for now is a state on their 22, on the 22 percent of their historical land. Now what happened in 1967, is that Israel occupied this remaining 22 percent of historical Palestine in what is known in our memory as the Naksa, the “setback,” and until now in the West Bank where I come from, we live under Israeli occupation- since 1987. Since day one of the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, Israel started building settlements, and the the Israeli settlements are ever expanding. Israel is the only state in the world without declared borders – their borders are ever expanding. They don’t stop building settlements. And now what is left for the Palestinians, now when we talk about where the Palestinians are living, for example, in the West Bank, we only have some form of government over 40 percent of the 22 percent of historical Palestine, which is under Israeli, under full Israeli control.

All of this area in in the last map where it says ‘today’, all of this area in white in the West Bank is, we call it “Area C,” and it’s under full Israeli control- It’s confiscated by Israel, and they were about to annex it, actually, at the time of the Trump administration, and these green bits here, maybe in the next map they are shown better- These are the green bits, now they are in red here. They are isolated pieces surrounded by Israeli settlements, divided by Israeli military checkpoints. More than 400 checkpoints separate all of these red areas, which are the Palestinian cities, surrounded by an eight meter high apartheid wall in areas like Bethlehem, and the 80 percent of this wall is built on Palestinian land, and sometimes it cuts deep in Palestinian land. So all of this area, so these red areas are just Areas “A” and “B” which are 40 percent of the 22 percent of historical Palestine, and the rest, the 60 percent of the 22 percent, is under Israeli military control, and there is where they continuously expand their settlements. So that is what is left of Palestine and that is what the Palestinians are fighting for, to build their, to build their state on, and this area is an area under occupation, like I mentioned.

It is marked by, like our lives, wherever you go in the West Bank, Israeli military checkpoints, apartheid wall, confiscation of land, settlements expanding continuously, families separated, like what my wife and I had to endure for two years or so, illegal military arrests, water shortages, and the list goes on and on. This is just in in a nutshell, a historical geopolitical summary of our history, what has been happening in Palestine, Israel, and how we experience it on daily basis in the West Bank at least.

Shadia Qubti

I just want to add a few points on Tony’s elaborate illustration, is the perceived notion that the Palestinian issue is very complicated, and rightly so with all of the different geopolitical divisions and fragmentations makes, that makes that very clear. But I also want to point out that any Palestinian that you meet will have their story of how that manifested in their own personal family’s journey and so it’s important to look at the 1948 Nakba or what Israel calls the War of Independence, is that it caused a huge alteration of Palestinian land, Palestinian life because Palestinian society was primarily agrarian, and so people lived in villages, and they depended on the land, and so when you take that, you cause a huge alteration of their economic, political, social life and you hear that when you meet people, and they’ll tell you their story from being farmers, where they had to go and what they had to endure, to where they are now, where their family is, but keeping in mind where they come from, like Tony is Bethlehemite, even though he might not be there now, but that’s where he comes from. I’m a Nazarene, that’s where I’m from, and so we have that connection to the land in our stories.

The second point I want to bring forth is that the trauma of what happened in the Nakba is still ongoing, it’s an intergenerational trauma. We all have that in our, in our family history, in our family stories, because history is written by the victorious and Palestinians’ history is primarily passed on through oral storytelling, or traditions of families.

And the third part, how that loss of land translates today is that Palestinians are fragmented into geopolitical entities. So there are about 10 million Palestinians across the globe today. Half of them live in what is more disputed and known as the occupied Palestinian territories which is the West Bank and Gaza. There are Palestinians who did not, were not, did not relocate into a proper Israel, but they were either internally displaced to another Palestinian village or city that was not, was not destroyed such as myself, so they’re called Palestinian- “Palestinians of 48” or there are more than 30 terms referring to the same people group. They’re about 1.5 million, they are citizens of the state of Israel. They constitute about 1.5 percent of the population. The third group that’s primarily the largest, is the Palestinian diaspora and so the journey of Palestinians who were relocated from the land of Palestine, they went first to neighboring countries and many of them spread across the globe. The largest Palestinian community outside of Palestine-Israel is in Jordan, and the third group and it’s a very group that’s usually forgotten, but they have their own geopolitical entity, East Jerusalem Palestinians, and that their citizenship, their status is usually contested, because they are a big demographical, they have a demographical weight. And so even if you’ve been to Jerusalem and you meet Palestinians, many of them, this is their hometown, they were born, their families were born there, but they don’t have any citizenship either in Israel or in Palestine.

So I think when we talk about Palestine- who are we talking about and who are the Palestinians, it’s important to note that each Palestinian you meet has their own story, and has their own experience of what Nakba means to them, what the Nekba has caused to their family.

Video 2: Peacebuilding in the Context of Palestine-Israel: Challenges and Prospects

The Notion of Peacebuilding in the Palestinian-Israeli Context

Tony Deik

Well, let me be the troublemaker here and problematize a little bit the notion of peace. When I first joined INFEMIT as a networking team member, I was asked to write a blog article for a famous, for a well-known progressive, evangelical American blog. And when I, when I wrote about, I chose to write about the pain and the suffering of the Palestinians. And the article was more of a call for repentance or a wake-up call for the evangelical church to look differently at what’s happening in Palestine-Israel. And when I, when I sent it to the editor he wrote me back and he sympathized with our struggle, and empathized, and etc., but he told me, “can you please tweak it to make it more pro-peace, pro reconciliation?” I didn’t mention the word ‘peace’ in the article, but he wanted to insert that word there, and when I told him the final telos, the final aim of the article is surely peace, but in this article I want to talk about the pain and the struggle of the Palestinians, and to make it as a wake-up call for the Western church. And when I told him this, when I told him, “Sorry, I cannot just insert the word ‘peace’ there, he basically apologized and he told me, “we cannot publish it.” He rejected to publish it- and this is not an isolated case, you know, when we as Palestinians and I would say maybe many other groups from the sub-altern, from the majority world, would I think share this experience. When we want to speak about our pain, we’re always demanded to speak about peace, and I would give you examples, a lot of examples from our context. You know, our books won’t get published, or articles won’t get published if we don’t speak about peace, our programs won’t get funded, if we don’t speak about peace. You know you cannot just open a master’s program about, I don’t know, the study of Christian Zionism, or justice, or etc. You need to put the word ‘peace’ here if you want to attract donors, if you want to, if you want to be listened to. But if we speak about human rights and justice, purely of course with the aim of achieving real peace and reconciliation, we are often not listened to unfortunately.

And this, this actually echoes a question that, a rhetorical question really, that Edward Said, the postcolonial critic, and really he’s the founder of postcolonial studies asked, “Since when,” he asked, “does a military occupied people have responsibility for a peace movement?” I find it unfortunate that oppressed people who are occupied, who are crushed, are then demanded, we are demanded to take the responsibility of making peace, you know what I mean. It is like someone gets abused or harassed and then the first thing that you tell them is that, “now it’s your responsibility to make peace. And not to make any peace, to make peace with the person who abused you.” And immediately without listening to your pain, to your story, without crying with you, just, you have the responsibility to make peace, you know? Like, and this is something I find it puzzling, you know? It is like when Peter Tosh, the Jamaican singer, the Jamaican reggae singer sang, “everyone is crying out for peace ,but none is crying out for justice.” Everyone wants to use, you know, the word ‘peace’ to the degree that we sometimes void it from its real meaning, even within Christian circles. Obviously Peter Tosh went on in his song, and said, “I don’t want no peace, I need equal rights, and justice.” I would say, “because I want peace, I work and advocate for equal rights and justice.” And I do not need to use the word ‘peace’ every time I speak about equal rights, and every time I speak about justice, and every time I speak about my pain, you know as a Christian, this is my final telos, this is my goal. God called me to be a peacemaker. But the peace of God, the real peace building of God is not a peace that trumps peace, that trumps justice, and trumps human rights. You know this, this kind of peace that is void of human rights and void of justice is not a peace that glorifies God. You know the peace that glorifies God is a just peace, is a righteous peace, the kind of peace that vindicates the oppressed and the marginalized rather than further oppress them. It’s a kind of peace that hears their stories, their pains, their struggles, not demand from the oppressed to take the responsibility to reconcile with their oppressor, and I think that this is especially important in the context of Palestine-Israel.

Last year, the Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi, to be more accurate he’s an American Palestinian now, he’s the Edward Said chair of Arab studies in Colombia University. He published a very well written book called Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, The 100 Years’ War on Palestine and he argued in it that our conflict, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, is unfortunately portrayed, at best, as a straightforward, if tragic, national clash between two peoples with rights in the same land. You know, even they call it always the “Palestinian-Israeli conflict” no?, as if there are two nations equal, you know, fighting over this piece of land, “al’ard” as we say in Arabic. Let’s solve this conflict, you know? This is a very misleading analysis of the history of the conflict, the so-called conflict. What has been going on for the last 100 years is not a national conflict. If you want to use the term ‘conflict’, okay, but it is a colonial conflict. There is a colonial power, one of the most powerful nations in the world, now- military and etc. A nuclear power supported by nuclear power, the nuclear powers of the world, and some of the most powerful nations of the world, the US and Europe and etc. Oppressing and colonizing and occupying Palestine and wanting to drive the indigenous people of Palestine out. This is what is happening. There is a power dynamic here, there is a power imbalance that sometimes we fail to notice. We just put the Palestinians and the Israelis on the same side, on the same level, as if there are two groups, two national groups fighting over a piece of land. It’s not like this, this is not an accurate portrayal of the conflict. It’s a colonial conflict. There is a colonizer and a colonized. And the question is, in this colonial context that is still ongoing, as I mentioned previously, Israel is the only country in the world with no declared borders. They are a state in continuous expansion. If you ask me Netanyahu or any Israeli politician to pinpoint where the borders are, they do not have any declared borders, they continuously expand. It’s a colonial state that is living. It never stops occupying other people’s land. And the question is: in this context of colonialism, of colonization, how do we do peace? And in particular, how can the church take its role as an agent of peace, in this particular context of colonization?

Shadia Qubti

Beautiful. I think I want to add to that- that the track record of peace in the Israeli-Palestinian context is very negative. I mean if you look at peace processes started ever since the Nakba, and for a Palestinian, if you look at all of the peace processes that even in the recent, the Trump peace plan, or before that- it’s a legal way to say, “we’re gonna take your land and give you less rights and you have to be okay with it because we’re doing it peacefully, we’re not using violence.”And so if you ask a Palestinian or an Israeli person, they would maybe- everyone wants peace, but what does peace mean, and what does that relate to the other side, is completely different. And we have to bear in mind that, you know, Israel has two peace processes with its neighbors, and in peace terminology, these are considered negative peace that means the lack of violence, but you know whether it’s peace with Egypt or peace with Jordan, there’s no relationship. There’s no cooperation except for “let’s not fight,” but you know, I don’t think this is this is possible to do with Palestinians because as you can see from the map that the Palestinian lives are, and the space, they’re so intertwined. You can’t really have this negative peace without asking a Palestinian, and not to ask for their same access and equal rights as their neighbor. And Tony touched on that as well- there is an imbalance of power. We cannot say that Israelis and Palestinians are equal. So when you want them to come to the negotiations table, you’re not talking about two equal entities. You have one side that’s very powerful on all aspects of life. I mean you know- we can look at the GDP difference between Palestinian and Israeli, even look at the vaccination right now, what’s happening in Israel and Palestine. It’s completely one very powerful side with one very weak side. So we can’t come and say, ‘let’s come and do peace together’ because this imbalance of power needs to be addressed. And in many ways, that’s why we have a third party- but that third party, unfortunately in the last decade, has not been neutral, and so already, that it just perpetuates the imbalance of power. There’s a lot of misinformation.

I’ll give you a story- when I did believe, I still do believe, that Palestinian and Israelis can live together. The problem is that there’s no willingness by the more powerful and the more decision makers, who can make, who can make the situation better, and so we bring Israelis and Palestinians together, they get to know each other, they form relationships. And one of the, [in] one of the groups, a person from Bethlehem had shared that they don’t have running water in their house every day. And they said especially in the summer, when it’s hot, they actually have less water. And so this person was sharing how they, you know, they don’t have enough water for their, for their needs. And this Israeli person was moved by the story, and he wanted to help, and so he said, “okay I’m going to go talk to my youth group and we’re going to go and buy some bottles of water and give them to this new Palestinian friend I have. And it was commendable for where they were, where they were coming from, and how they wanted to take action for the need of their Palestinian brother had. But it made me think- why not address the issue of lack of water systematically, rather than just provide a few bottles of water that are going to be running out in a week or so? And so there is a misunderstanding of what, when we come to peace building, we want to change. Palestinians want to change the situation, because the more they wait, the more they suffer, the more they are paying the price of this current status quo. And so there is the sense of urgency that- I can’t wait till my Israeli counterpart to understand, to get up to date, to understand the context, to realize how much he’s benefiting on my expense, and then once they realize that they want to take action, and they et cetera et cetera. So there is this sense of urgency- that the peace we want, we wanted to address the systematic imbalance of power, imbalance of access to resources, of rights, which consequently affects how we live and how we can co-exist side by side.

Tony Deik

Shadia, the example that you gave is really powerful, because sometimes we want to solve injustice by charity. Injustice isn’t solved by charity. Injustice is solved by tackling the roots of it, by tackling the roots of oppression. And injustice is solved systemically. You know?

Shadia Qubti

Absolutely. And sometimes, you know, we want to feel good so, we want to put a band-aid on the wound, and you know, here’s a little band-aid ,you can use it! But we want to address why is it there, like, how can we heal this wound from staying? Rather than just looking at the surface. And I think that’s the attractiveness of the word ‘peace’- is that it sounds great, it’s lovely, and everyone loves it, but are you willing to pay the price to really reach a peace that is just for both? That reflects that both sides can live side by side rather than one on the expense of the other?

Tony Deik

It’s a word that everyone uses- from Donald Trump up to Miss Universe, when they ask her, “what do you wish? – I want world peace!” No, we need to really be precise and define what we mean by peace.

Challenges to Peace Building in Palestine Israel

Tony Deik

Yeah, so for me, the first challenge is that in this colonial power dynamic, the church is taking the wrong side. Rather than standing with the oppressed, the evangelical church in particular, stands with Israel, the colonial power. And not only that, evangelicalism is providing a whole theological system, Christian Zionism, that legitimizes and justifies the ongoing occupation of Palestine- describing it as an act of God in a way, not very different from how Christians justified slavery in the past, slave trade, colonialism in other parts of the world, and all of the, sadly all of the atrocities that Christians committed in the name of Christ, and the Bible. And maybe Christian Zionism, the only difference is that it’s more complex than other colonial theologies, and it covers a wider range in the church. There is a liberal Christian Zionist theology. Evangelicals have their dispensationalist Christian Zionist theology, so it is I think, a bit more complex than other colonial theologies, but nevertheless, it is used to oppress and to colonize the Palestinians.

So for me, the first challenge is the challenge of theology, is the challenge in particular of Christian Zionism. The church cannot take its agency of peace, cannot fulfill its mission as an agent of peace, without getting rid of Christian Zionism.

Shadia Qubti

I remember it was during one of the, beginning of 2000- there was war, there was a war Hezbollah was shooting rockets on Israel, and I was in Jerusalem, and we were in a prayer group. I went with my friend and you know at times of war, you pray, I mean that’s what you can do is just pray. And I remember I was in a small group and this one of the members started praying very passionately and he said, “God protect your people Israel and do not let these missiles launch and touch them. Let these missiles go to Jordan, to Egypt, anywhere but to Israel…” And you know, this person was praying, and I was conflicted because, why are we praying? Are we praying to just protect one group from the other? I mean, why not pray for the stop, to stop this? Or why are we praying and not praying enough to peace for all people? For changing your heart on both sides? And after the prayer I approached this person and he said, “well because this is God’s people. This is, we are Israel, and God will protect them.” And I said, “Well what about the Palestinians? What about the Jordanians?” “I don’t care about them, like, it’s about it’s about Israel.” And so I think Christian Zionism has really created a situation where we as Christians, as believers, we are taking sides, and we are seeing things in a black and white, a black and white way, that for me, as a Palestinian, it doesn’t reflect my understanding of who God is. It doesn’t reflect how I see my faith play a role in my context. And I think Christian Zionism places the situation in a very black and white- where there’s good people and bad people, and God is on one side, and not on the other side. And I think simply by being a Palestinian Christian, when you’re saying, “wait a second- you know, God is not on one side or the other. God is with justice. God is with peace.” And where is that? And what does that look like? And so I think in many ways, Christian, many people who are not from my context, are more familiar with Christian Zionist understanding of the Bible or how to view Israel today. And in many ways when we, when I get a chance to go and speak about my experience, my life, I’ve had situations where I just said, “Hello, my name is Shadia. I’m a Palestinian.” And someone just stands up and saying, “There’s no such thing as Palestinian.” Or when I went to a worship concert and the organizers recognized everyone there except for Palestinians, when they were asked repeatedly- There’s Palestinians- They just don’t care. So I have to be careful and mindful. That if your theology is rejecting or giving you a sense that “these people are bad, or these are good,” I think you need to reconsider that theology, and look at areas where you can be more informed and more understanding of the context.

Tony Deik

I think the best definition and the simplest maybe of Christian Zionism is that of Colin Chapman. He defined Christian Zionism simply as, “the Christian support of Zionism that is based on theological reasons, on Christian theological reasons.” And the term ‘Zionism’ in general, as I mentioned, refers to the Jewish national movement founded by Theodor Herzl in 1897. But at least 60 years prior to Herzl’s Jewish Zionist movement, Christians started paving the way for the Jewish colonization of Palestine and what came to be known as Christian Zionism. Some scholars like Stephen Sizer trace the origins of Christian Zionism to John Nelson Darby and his dispensation theology that separated church from Israel. And others like Robert Smith, for example, trace it further back to Protestant Biblical interpretation of the 16th and 13th centuries. Regardless of the theological and historical roots of Christian Zionism, Christians provided both theological justification and active support for the return of the Jews to Palestine at least since the 19th century, way before the Jewish Zionist movement was founded. Christian support was actually so essential that some argue that if it were not for the activism and commitment of key Christian figures in the 19th century, the modern state of Israel might not have been established. For example, contrary to popular belief, the infamous slogan used by Zionists to colonize Palestine, “A land without people, for the people without land,” was actually first coined by the Christian clergyman in 1843, long before the foundation of the Jewish Zionist movement. This Christian support of Zionism took then a more radical turn after the establishment of Israel in 1948 and especially after the 1967 six-day war, which is often remembered by Christians as a miracle of God. And today, for many Christians, especially among evangelicals in the West, they simply believe that Zionism and Jewish restoration to Palestine are simply part and parcel of Christianity.

A Way Out and a Way Forward

Tony Deik

Yeah for me, I think, as someone dedicated to studying and teaching the Scriptures, I see the solution there, or at least I infer Biblical models to find a way out. And in particular, the challenge of Christian Zionism, when it comes to the agency of the church and to the mission of the church, of peace building, this kind of challenge, the challenge of theology isn’t new. If you remember in the book of Acts, the church couldn’t preach the Gospel of peace to the Gentiles until Acts chapter 10, that was the first sermon, the first evangelistic preaching delivered to the gentiles by Peter in the house of Cornelius. And that, and that incident is very, very interesting because Peter specifically says that he is proclaiming the peace, you know, the peace that comes by Jesus Christ in Acts chapter 10. ‘I come to you preaching peace by Jesus Christ, He is Lord of all.’ But what’s interesting in the story, that before Peter could preach about peace to the Gentiles, an internal theological transformation that’s actually key to the history, to the history of the church and mission, you know, we’re not talking just about the Biblical text and isolated Biblical text. This is a crucial moment in the history of mission and industry of the church. That before Peter could preach the Gospel of peace to Cornelius and his household, a theological transformation needed to happen. And what happened is two things, actually. God had to change his theology, proper, the way he understands God. And he had to change the way he looks at the Other before he could preach peace to the Other. So when Peter enters into the house of Cornelius, if you remember the story, first, God shows him that. And this is Peter speaking- “God has shown me that I should not call anyone profane or unclean.” And to understand this, we need to understand a bit of the context of what was going on there. The early Christians, the Jewish Christians in the first century, we like to, we like it or not, they had a kind of an ethnocentric theology that views God as the God of the Jews, and they are the chosen people of God, and other people are outside, other people are profane or impure and are unclean. So in order for Peter to be able to preach the Gospel of peace to those people, God needed to change the way he looked at those people. You know, the way he looked at the other not as less, not as unclean, not as in impure, but as equal. And the book of Acts says, the book of Acts elsewhere, in Acts 17, the Others, the non-Christians are actually described as God’s children by Paul in Acts 17. So that view of the Other needed to change first, the way he looked at the Other, and second, when he started just before he started preaching the Gospel in the house of Cornelius, Peter, the text says, “Then Peter began to speak to them: ‘I truly understand that God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to Him.” So basically, what’s happening here is that his theology, his theology proper, the way he understands God, needed to be changed from an ethnocentric view of God, an ethnocentric understanding of God as a God of favoritism, as God who prefers one people over the other, to a God that is inclusive, that welcomes everyone regardless of their blood, regardless of their color, regardless of their race. So these two things that are in the core of the theology of the church needed to be transformed, their theology needed to be deconstructed, if you want to use modern terms, their theology needed to be deconstructed and transformed. They couldn’t have preached the Gospel and be peacemakers and peace proclaimers without transforming the way they look at the Other and the way they understood God. Only then, and the text is very clear, this, all of this happened before, and only then, Peter could pray to the Gospel of peace. So the way out, or a way out of Christian Zionism is the deconstruction of this theology, is the transformation of this theology. Our God is inclusive, he does not distinguish, and Peter says it clearly. Two thousand years ago the church discovered this, the church had had this theology two thousand years ago. I now realize 2000 years ago, that God does not show favoritism. That’s the solution to Christian Zionism. It’s as simple as this, we need to go back to our simple, to our Orthodox Christian doctrine, you know? And our Orthodox Gospel.

And the second challenge, the challenge of context for me, I find a very good model. And this is the paper actually that I shared last year in our consultation back in 2019, the past INFEMIT consultation, is that I find the model to the second challenge in the wisdom tradition of the Bible. And why the wisdom tradition? Because unlike other Biblical books, the wisdom tradition, the epistemology of the wisdom books is very empirical- ‘I look, I see, I see how the ant walks, and I deduct from there with my God-inspired mind,’ you know? ‘I see and I learn from experience, from what I see in front of me, and in, and in particular, the book of Ecclesiastes is very big on this. Like the word ‘see’ in Hebrews repeated in the book of Ecclesiastes 47 times. The guy just goes around and sees things, you know, and he learns from it. Now unfortunately, some scholars, and among them, evangelical scholars, they don’t think that the core of the book, you know, you know what ‘Koheleth,’ the preacher, or the teacher speaks in the core of the book is something normative. They say that the normative message of the book is in its epilogue, which basically destroys all of the core of the book. This is what they argue. Why? Because the book depends so much, the epistemology of the book is so much based on an empirical method, you know? ‘I see, I see, I experience, and I deduct,’ so they claim, they argue, that actually the whole canonical value of the book, the whole normative message of the book, that this epistemology is not the way, you know? God does not want us to use the empirical epistemology, he wants us to use more revolutionary epistemology that is based on a revelation from God, or what He says, that’s root, that is rooted on God. But I would argue otherwise- this empirical epistemology is rooted on God, you know? It’s Koheleth, it’s the teacher, in the book of Ecclesiastes, is using his mind and his eyes to see. And what’s interesting in our discussion is that what he sees, and among the core things that he sees is injustice, you know? And what is striking for me is the way that he analyzes injustice, just if we can show these two verses on the screen from the end of chapter three of Ecclesiastes and the beginning of chapter four, allow me to read them, from the NRSV edition, Koheleth says, the teacher, “Moreover I saw under the sun that in place of justice, wickedness was there, and in the place of righteousness, wickedness was there as well… I saw all the oppressions that are practiced under the sun. Look, the tears of the oppressed– with no one to comfort them! On the side of their oppressors there was power– with no one to comfort them.” Now unfortunately, many Western commentators are quick to declare that here, Koheleth is only descriptive, you know, here the text is only descriptive. Koheleth just notices injustice and oppression, but he doesn’t do anything about them. But if you dig a little bit deeper, what Koheleth is doing here is tremendous. Koheleth is understanding the cause of oppression and injustice. He says specifically, the reason for the injustice is clearly, is explicitly mentioned in the text. It is not the sin of the oppressed, you know, Koheleth, unlike us, does not point to the oppressed and tell them, “it is your sin that you are being oppressed.” Rather like an intellectual with penetrating analysis, he recognizes the power imbalance between the oppressor and the oppressed as the cause of the affliction of the downtrodden. On the side of their oppressors, there was power. And he also understands that this is part of a bigger system of oppression, or a hierarchy of power which goes all the way up to the king himself, and he says this clearly in Ecclesiastes chapter 5 and verse 8- If you see in a province, the oppression of the poor and the violation of justice and right, do not be amazed at the matter, for the high official is watched by higher, and there are yet a higher ones, higher ones over them. This oppressive hierarchy of powers for Koheleth, for the teacher, the preacher, is the cause of the oppression of the poor and the violation of justice and right. So from the, what I’m trying to say is that from the wisdom tradition, from our wisdom tradition, because it’s so empirical, it grounds us, it puts us on planet Earth. It has us open our eyes, see injustice, and analyze it for what it is. So I think there are Biblical models that provide a way out for the challenge of Christian Zionism, basically the deconstruction of ethnocentric theologies and their transformation into an inclusive Christ-centered theology, and second, the wisdom, the Biblical wisdom tradition provides us a wealth, provides a wealth of insight on how we should look and analyze what is happening in front of our eyes.

Shadia Qubti

I think for me, and this is one of the most difficult questions to ask, because again I think very grounded in my theology and understanding of what God’s mission for us is here, and how we are to be peacemakers, and to advocate for peace with justice with equality, but on the other hand, reality is very harsh. Reality is always stomping you down, and I think even, you know, personally for me, you know, how do you move forward? How do you keep going? And to balance our theology of hope, but a reality of hopelessness? And there’s always this challenge to navigate these two, especially as things seem to be regressing on top of the current situation. And I think partly, it’s also, yeah, I’m saying that on one hand, but I also acknowledge that we are people that is, that is known for its perseverance. We keep going, you know, living under empires is part of our who we are, and we’ve managed to kind of survive throughout it. So we have that history, and that that traditional wisdom of how to keep going, especially when things are difficult. And I think it’s also partly where I am right now. I’m kind of trying to, I’m studying more into indigenous theology and trying to kind of learn, you know, how to be, how to understand marginal theology- where’s the power, and that the inspiration of that, and take it into my context. And then I think, you know, just from this, some of the work that I tried to think about is the Palestinian tradition is so rich and it’s so beautiful with how much it’s it speaks about connection to the land, connection between the people, especially the way our, my matriarchal ancestry told stories through embroidery, through food. I mean there’s so much written richness there, and I think, you know, my learning of indigenous theological lens has helped me see that. And I think that gives a lot of hope, that gives a lot of inspiration to continue that legacy, to continue telling stories. And it’s partly, I think this is an area that I’ve been very passionate about, and I’ve been involved in. Many of my experience is to tell stories, because everyone has a story to tell and that’s important and it’s very powerful. And one of the examples is the podcast that I co-produced with two of my friends- that we wanted to hear Palestinian Christian women’s experiences and how they experience the conflict, how they, how they intersected with their gender and their faith and so it’s lovely, you know? 30 minutes of storytelling of different women, different, different situations of life and how they navigate their context. And I would encourage you to kind of, if you want more stories, more areas to connect, to understand where people come from, especially the complexity of the Palestinian context, stories help give you an entry point to that. But it’s not the end point, it’s only the beginning and I think another way forward is to also keep in mind that, remind myself that, I’m, we shouldn’t be result-oriented, but journey-oriented, right? It’s not just, it’s not just seeing peace, or wanting to get, if I don’t see peace then it’s not happening, but have faith that it’s the journey, and each one of us has a role to play, roles to do, and God takes care of the full picture, and kind of do our things. But it’s very, it’s very challenging, it’s very hard, especially hope. I think keeping hope going, it’s a daily decision, and it’s something that’s very real because I’m sure you have similar experiences. You turn on the news, and it’s all bad news, and so how do you, how do you keep going, but I think it’s also, we have the tools for that, we have the theology that helps us inform our knowledge about how to move forward.

Leave a Reply