Reflections on the Opening Sessions of Stott-Bediako 2020

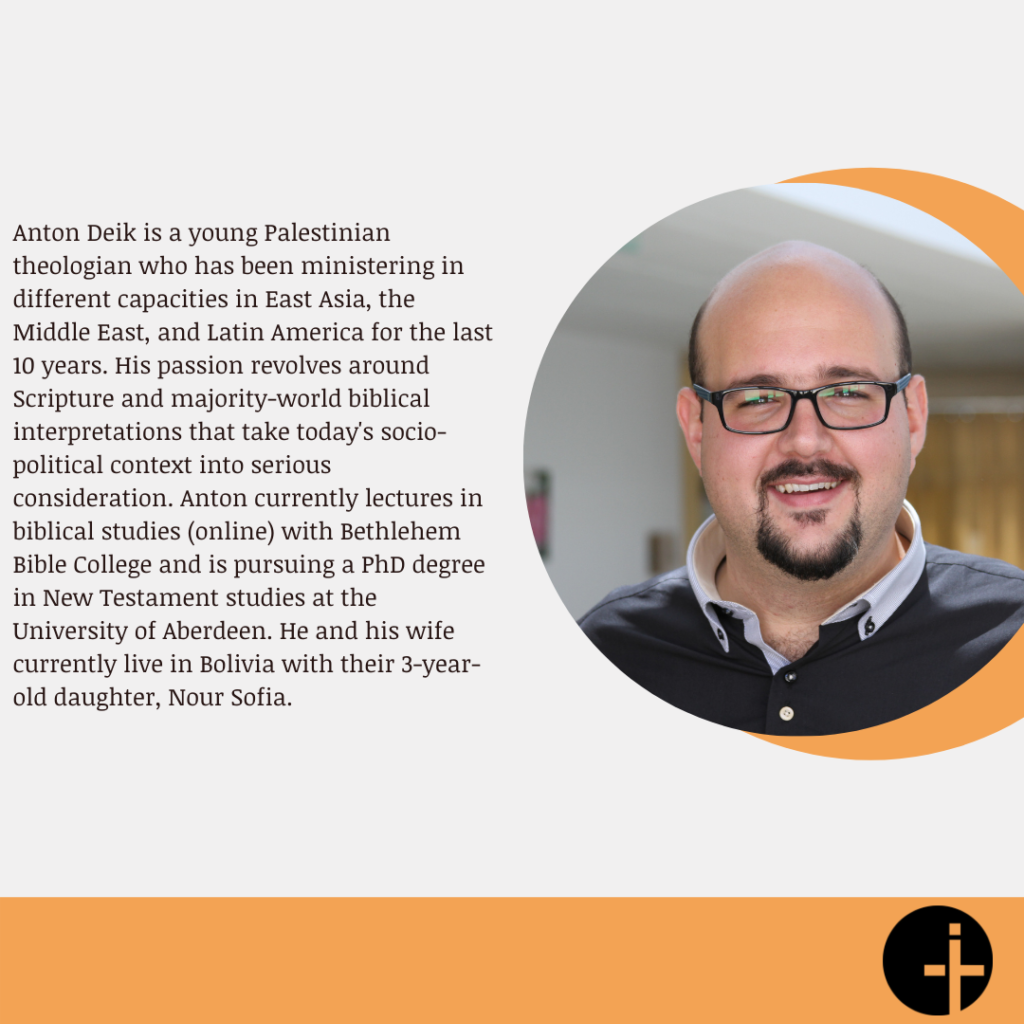

by Tony Deik

Presented for the Stott-Bediako Forum

Palestinian academic Edward Said is known to be the father of postcolonial studies. In his seminal work, Orientalism,[1] Said explains how Western colonialism, especially in the nineteenth century, was legitimized by anthropological theories that portrayed the world as made of two unequal halves: those who dominate, and those who are dominated. Those who dominate, according to these theories, are the enlightened, civilized, and rational; those who are dominated are the irrational, backward, and inferior—the childlike who require the guidance and tutelage of the West. In postcolonial terms, the colonized are viewed as “perpetual students” requiring the West’s “paternal rule,” “for their best interest.”[2]

Unfortunately, while such theories provided anthropological justification to colonialism, the Western church provided theological legitimization. In Latin America, for example, early Catholic missionaries and theologians were not able to see God’s hand in the lives of the natives. They were, however, readily willing to discern God’s work in the bloody Spanish conquest and colonization of the land. They saw themselves as the enlightened, rational Christians coming to civilize and Christianize the irrational, savage natives. African American theologian, Willie Jennings, calls this “pedagogical imperialism,” where natives are to be taught submission to Western Christian tutelage, as native cultures and traditions are dismissed as ontologically inferior and demonic.[3]

As much as it is painful to hear, this is not mere history, but a continued reality. Both colonialism and its theological legitimization are still ongoing today in many parts of the world—albeit at times in new forms and practices. In my own context of Palestine-Israel, Christian Zionist theologies (both liberal and conservative) continue to provide biblical and theological legitimacy to the ongoing Israeli occupation of our land. Palestinian theologian Mitri Raheb calls such colonial theologies “the software” that enables the war machine of the colonizer.[4]

Despite this, there is light in the midst of darkness! As I was listening to the opening sessions of this year’s Stott-Bediako forum, I felt a deep sense of hope coming from the body of Christ. The forum, for me, undermines pedagogical imperialism, and instead embodies a world that is upside down—like that of the early Christian movement. In this Gospel-centered world, the subalterns and natives come not as inferiors to be taught, but as contributors to be listened to and learned from; and Western sisters and brothers come not as “perpetual teachers” but as fellow pilgrims—siblings with whom we share koinonia (fellowship) in Christ.

In the opening sessions of the forum, we heard Jocabed Solano, an indigenous Guna voice, calling upon the church not only to dialogue with indigenous theologies and practices, but also to recognize “the historical context and current realities of the peoples who have survived and resisted colonialism’s multiple types of violence up until today.”[5] We also heard from Quechua Ecuadorian Julián Guamán Gualli and American Mennonite missionary Peter Wigginton as they shared a Quechua/Mennonite perspective on peacebuilding that includes all of God’s creation.[6] Rooted in a collectivist indigenous culture, they offered a theological perspective that, in my opinion, is closer to the original Palestinian context of the Scriptures. The opening sessions of the forum also featured theology done through art. Daniela Amestegui, a Bolivian artist, presented a sophisticated work of contextualization in which she presented the full liturgical calendar using Andean artforms, images, and colors, and through that translated the underpinning biblical narrative to Andean language and culture.[7] It is worth mentioning that all this is only the beginning of Stott-Bediako 2020! Coming up are voices from North America (including first nations), Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East—so stay tuned![8]

Stott-Bediako’s koinonia-in-diversity constitutes what real, genuine peacebuilding means—the kind of peacebuilding the church is called to model for the rest of the world. This peacebuilding is rooted in the God of the downtrodden and marginalized, who “brings down the powerful from their thrones, and lifts up the lowly” (Luke 1:52); it is Christ-centered, announcing the good news that God “shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him” (Acts 10:34–35); and it does not trump justice and truth, but is rather where “righteousness and peace kiss each other” (Psalm 85:10).

[1] Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

[2] For an excellent introduction to postcolonialism, see Robert J. C. Young, Postcolonialism: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[3] Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 95, 112.

[4] Mitri Raheb, Faith in the Face of Empire: The Bible through Palestinian Eyes (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2014), Chapter 2: A Prelude to a Palestinian Narrative.

[5] You can watch Jocabed here (with other voices of Memoria Indigena) and here (in her plenary talk).

[6] You can watch their conversation here (part one) and here (part two).

[7] You can watch Daniela here.

[8] This Stott-Bediako Forum has now ended, but you can find much of the content on INFEMIT’s website. You can also sign up for our emails to receive notifications about future opportunities.

The views and opinions expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect an official position of INFEMIT. We seek to foster reflection through conversation, and ask you to be respectful and constructive in your comments.

Leave a Reply